Andy Jassy may be the continuity candidate following in Jeff Bezos’s footsteps, but it’s not all wine and roses in Amazonia. Here are 9 key strategic challenges facing the new leadership at Amazon. Here’s my short strategy assessment at Technical.ly

Bezos goes, Amazon booms, but the real story is the Marketplace

Amazon has been all over the news the last 24 hours, with Bezos stepping down and Amazon roaring past $100 billion in revenue in Q4 2020. Those are both important stories – but under the hood, it’s the accelerating shift away from Amazon retail and toward the Amazon Marketplace that really matters.

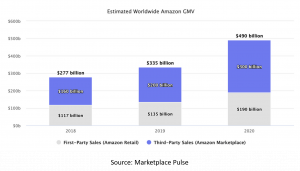

The chart below from Marketplace Pulse tells the story. Total GMV (sales) across the Amazon retail platform reached almost $500 billion. Marketplace sales are up 50% – even though non-essentials sellers were deprioritized in favor of COVID necessities. So Amazon’s total sales have almost surpassed Walmart, and will do almost certainly in 2021. Another year like 2020 and Walmart will be receding fast in the rear-view mirror.

But there’s an even more important important story here. Amazon is continuing it’s shift away from its own retail operations (Amazon retail), towards its enormous third-party Amazon Marketplace. Over the past 15 years or so, that shift has averaged around 2-2.5% annually. In 2020, the Marketplace share reached more than 60% for the first time, at 61.2%.

This ongoing shift is not surprising. Amazon retail loses money – a lot of money – as I show in Behemoth, Amazon Rising. Conversely, Marketplace made about $17.8 billion in operating revenue in 2019, a margin of 33.1%. It makes perfect sense for Amazon to transition away from its own retail business and into it’s increasingly dominant role as the platform manager.

Amazon and Autonomous Vehicles

Amazon is up to something in autonomous vehicles (AV) – is it really looking to deliver by drone, especially for groceries? That’s part of the story.

Groceries: Amazon’s Afghanistan?

In 2017, Amazon bought Whole Foods. Since then, it’s opened a handful of new Amazon Fresh grocery stores and plans many more, along with Amazon 4-star stores, small cashier-less Amazon Go convenience stores, small Amazon Go grocery stores, and a few physical bookstores. It’s diving deep into physical retail, focused primarily on groceries.

Plenty of excitement, then. But sadly misplaced.

Amazon has no business being in groceries at all. Take it from one who knows. In his 2005 letter to shareholders, Jeff Bezos said this: “I often get asked, “When are you going to open physical stores?” That’s an expansion opportunity we’ve resisted. It fails all but one of the tests outlined above. The potential size of a network of physical stores is exciting. However: we don’t know how to do it with low capital and high returns; physical-world retailing is a cagey and ancient business that’s already well served; and we don’t have any ideas for how to build a physical world store experience that’s meaningfully differentiated for customers.”

So have things changed since 2006? Not really. Grocery stores are high capital/low margin projects. Unlike books and electronics and even apparel, there are no fat and happy bricks-and-mortar incumbents with tempting margins. On the contrary; the groceries pool is filled with great white sharks. So where are Amazon’s competitive advantages? There aren’t any:

- Amazon’s huge competitive advantages online mean nothing in groceries. That enormous catalog and the great search and recommendation system doesn’t matter much… milk and eggs is milk and eggs.

- Amazon’s extraordinary logistics network is tuned to goods, not groceries. Doorstep delivery costs make free delivery unsustainable, Amazon has no competitive advantages here anyway, and Whole Foods stores are not well placed to act as delivery hubs.

- Amazon’s past record in groceries is poor: Amazon Fresh – its long-running grocery delivery service – has gained no traction. And Whole foods at best breaks even.

Amazon has no expertise in groceries, no track record of success, and will be running uphill against bigger and more experienced competitors with much better supply chains, and with deep established relationships with both suppliers and customers.

But what if Amazon builds the grocery stores of tomorrow, not today? Maybe Amazon is betting on the grocery business of 2031, not 2021. That means automation behind the store, through automated stocking systems like Ocado’s; automation within the store, through cashier-less tech like Amazon Go; and delivery to the home, likely through more AVs such as the Scout that Amazon is testing now in Tennessee. Automation will cut costs, perhaps significantly. However, it’s being heavily pursued by other grocery chains as well, so won’t provide Amazon with a significant or durable advantage.

Still, the real train-wreck comes from huge organizational and financial challenges. A medium-sized grocery does about $554,000 in weekly sales ($28 million annually).To match the scale of Aldi’s – the 4th largest US groceries chain with about $31 billion in revenues, Amazon would need about 4,500 average-sized supermarkets. But this not digital, with effortless scaling. It’s a physical business where every store needs a location, staff, local buy-in, and regulatory approvals. Every individual store is a challenge.

Assume that somehow Amazon sprinkles magic dust and builds a network of 4,700 supermarkets in the next few years. Running them is an enormous undertaking. Each store comes with dust and rats and physical problems to be solved every day. And there’s no evidence that Amazon has a secret formula: Whole Foods is break even at best.

Leaving the standup and operational problems aside, if somehow Amazon became as successful as Aldi, that still wouldn’t move the needle. Aldi’s 2019 profits were about 1.4% of revenues, or about $430 million. That’s barely 3% of Amazon’s operating income.

Amazon may have other reasons for getting into groceries. Maybe it just wants to prove and then license technologies. But Bezos is still right. Groceries is a high cost/low margin business with well-established competitors, where Amazon has no sustainable competitive advantages. It also requires huge startup costs and offers low returns. That’s why groceries could become a quagmire for Amazon: a huge long-term financial and energy drain, with low and uncertain returns. Perhaps Bezos should re-read that letter.

To receive an expanded version of this post plus other news, signup up for the weekly Amazon Rising newsletter at substack.

Will Amazon become the next FedEx? No, it won’t.

Jay Greene just posted a well-researched piece on Amazon logistics in the Washington Post. Lots of good stuff that I plan to use. But a central theme of the article is that Amazon is positioning itself as a competitor for FedEx/UPS/USPS. I don’t think that’s correct.

Continue reading “Will Amazon become the next FedEx? No, it won’t.”

Amazon and Rural Deliveries – the Story Behind the Story

Amazon recently revealed that it was planning to undertake more rural and super-rural deliveries, replacing USPS and UPS with its own service. The cutely named “Wagon Wheel” project is on the surface completely ridiculous. It makes no real sense for Amazon to compete in precisely the places that are most expensive and least profitable. Indeed, to date it has avoided those routes like the plague.

So what’s going on?

Continue reading “Amazon and Rural Deliveries – the Story Behind the Story”

About that COVID-related “productivity drag” at Amazon

Amazon’s CFO recently explained that about $4 billion quarterly in additional costs during the third quarter were driven by unspecified “productivity drags” related to COVID-19 had cost the company $4 billion in the third quarter of 2020. What does that mean?

As usual, Amazon conceals more than it reveals. Maybe it’s all about clusters of sick people in the warehouses desperately moving packages around until they collapse and die. Fortunately (for them and us), the reality is different. Continue reading “About that COVID-related “productivity drag” at Amazon”

Antitrust and private labels at Amazon: wrong solution to the wrong problem

Amazon recently got a ton of bad press about its private label brands at the recent House Subcommittee hearing. It was blasted for using sellers’ data to cherry-pick products that it could then directly source (sometimes from the same manufacturers), using its size to brush smaller competitors aside. There were further complaints that it tilts the playing field to force sellers to use Amazon fulfillment, or to tweak the Buy Box in Amazon’s favor.

This is a mishmash of complaints, and the private label arguments are basically ridiculous. Continue reading “Antitrust and private labels at Amazon: wrong solution to the wrong problem”

Unpacking Amazon’s free curbside pickup

Obviously, someone at Amazon has noticed that Walmart and Target are getting traction with curbside pickup. Hence Amazon’s announcement that it will provide free one hour pickup from Whole Foods for orders of $35 or move (and who leaves Whole Foods without spending at least that much). So on one level, this just reflects me-too insurance, so if curbside really takes off Amazon won’t be blindsided.

Continue reading “Unpacking Amazon’s free curbside pickup”Amazon’s cash gusher – compulsory advertising on Marketplace

According to Pacvue, an ad management platform for Amazon, the cost per click of advertising on Amazon was up 23% on Prime Day, year-over-year. This is a very big deal for several reasons. Most obviously, it means that more advertisers are competing for good slots. That’s good news for Amazon, which has dramatically increased ad inventory in the past 4-5 years, but this means that much more inventory hasn’t even kept up with demand. Continue reading “Amazon’s cash gusher – compulsory advertising on Marketplace”