Originally published in CEOWorld February 12 2022

Retail is, conceptually, pretty simple. A retailer buys in stock, marks it up, and sells it to a customer. When executed well, the retailer makes money – enough to pay for business operations, a profit, and the items that didn’t sell. That model goes back at least 3,000 years, and it’s still the dominant model today.

Of course, there are variations. Sam’s Club and Costco, for example, charge a modest annual fee, which adds to revenue. Big retailers have learned they can charge (a lot) for prime placement within the store. In some industries, retailers have imposed sale or return policies – publishers know they have to offer booksellers the option to return unsold books if they want those orders to keep flowing. Still, the basics are still pretty simple: overwhelmingly, revenues come from sales.

Amazon is different. It has developed a new retail model, where revenues from sales are only one of four important revenue streams. TAs a result, revenues from customers are a much lower percentage of total Amazon Retail revenues, which in turn allows Amazon to charge those customers lower prices. Obviously, this is a huge advantage.

How does this work?

Amazon’s retail operations are really two businesses under one roof. It has an enormous traditional retail operation (“Amazon Retail”), growing out of its origins in books and then toys and electronics. This traditional retail business generated almost $200 billion in sales in 2021. In some segments, Amazon dominates – for example, it accounted for more than 50% of all books sales in the US. But there are only a handful of similar segments. In most, Amazon faces significant competition.

The second business is the Marketplace – the online souk where 2 million active sellers from all over the world connect with Amazon’s customers. From Amazon’s perspective, the Marketplace is a mall and Amazon is the mall operator. Amazon doesn’t buy or own the inventory, which is actually sold by those millions of sellers. Amazon’s job is to facilitate, by acquiring customers, guaranteeing satisfaction, enhancing the flow of information (reviews), and of course supporting delivery through its incredible logistics network. And from the customer’s perspective – and by Amazon’s design – it’s difficult to differentiate between the two businesses.

Amazon generates enormous revenues and operating income from the Marketplace, in three ways: from a straight commission on all sales, which is mostly 15% of gross sales; from sellers’ increasingly mandatory need to advertise (ads get you prime placement on Amazon’s search results page); and from fees associated with Amazon logistics.

For Marketplace sellers, those losgistics fees are mostly a pretty good deal, though they have been increasing steadily. For small sellers, Amazon logistics is hugely convenient, while larger sellers often split their logistics between Amazon and other providers (including their own warehouses). Amazon also benefits from the enormous economies of scale that flow from combining the Marketplace and Amazon Retail, which together now account for more parcel deliveries than FedEx.

But If little operating income flows back into Amazon from logistics, that’s not at all true of advertising revenues or the annual subscription fees for Amazon Prime. Along with the commissions generated via the Marketplace, advertising and Prime heavily subsidize the nominal price charged by Amazon Retail.

How big is that subsidy?

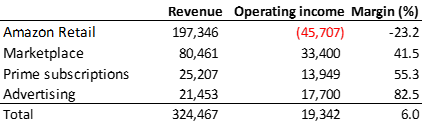

Amazon’s financial books are designed to obfuscate, so Amazon doesn’t directly explain the profitability of each business segment. But it’s possible to make some good estimates. For 2020 (pre-pandemic), those estimates look like this, after subtracting the costs of delivery for both Amazon Retail and the Marketplace (there is a detailed analysis of Amazon’s financials in my book Behemoth, Amazon Rising):

Source: Robin Gaster, Behemoth, Amazon Rising

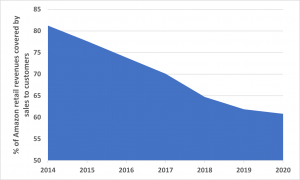

Amazon ekes out a modest profit from retail operations as a whole, but these multiple revenue sources let Amazon Retail sell at prices that are significantly below cost, subsidized by income from Prime, advertising, and the Marketplace. In fact, Amazon Retail revenues only covered about 60% of Amazon Retail costs in 2020, and that share has been steadily declining, as Amazon’s new retailing model supplants traditional retailing:

Source: Amazon annual reports; calculations by author

These kinds of cross-subsidy have attracted anti-trust attention in the US, going back to the original trust busters in the later 19th and early 20th centuries. Cross-subsidies can be unfair to competitors who don’t have deep alternative pockets into which they can dig.

But – again – Amazon may be different. Rather than cross-subsidies from unrelated businesses, it has built a complex new retail ecosystem, a new model, in which customers are well served at prices that are driven down, not up, by relentless competition.

Inside its platform, Amazon cannot just eliminate its competitors and raise prices like Standard Oil. It’s definitely true that at the micro scale, Amazon is often anti-competitive (see for example Jason Boyce’s testimony that Amazon chased him out of one profitable niche business after another). But at the aggregate level, Amazon operates in a highly competitive environment, and creates new opportunities for small retailers that simply did not exist before Amazon emerged with its extraordinarily low barriers to entry and immediate access to hundreds of millions of potential customers. Indeed, the massive lake of red ink at Amazon Retail is indisputable evidence that the Amazon platform is profoundly competitive.

However, Amazon’s new model offers a massive challenge to other big retailers; none of them have those multiple revenue streams on which to draw. Prime has more US accounts than there are US households (172m and growing). Walmart has Sam’s Club, but that has fewer than 50 million members and charges only $45/year, while Amazon is about to increase the annual fee for Prime fee $139.

Similarly, all the big retailers charge placement fees in their stores, but those are a drop in the bucket compared to the enormous profits flowing from Amazon’s $31 billion advertising business (estimated margin is >80%). And none has a significant online advertising business.

Worst of all, the other big retailers have totally failed to build a competing Marketplace. That’s really damaging, given that gross merchandise volume on the Marketplace is now nearing $400 billion, so Amazon’s commissions must be nearing $60 billion. As a result, Amazon added more to its total GMV in 2021 ($1110 billion) than Walmart and eBay did in total worldwide e-commerce sales combined.

Retail success is often about scale and financial muscle. By building an entirely new model for retail, Amazon benefits from massive and fast-growing funding inflows for its retail operations. How Amazon chooses to use that remains to be seen (so far, a lot has gone into building out logistics and AWS). But it’s ammunition that other retailers simply do not have and will not develop.