Obstructive sleep apnea is a potentially dangerous disease. As the airway closes during sleep, it causes victims to wake up repeatedly, often with a loud snort. It also causes heavy snoring, which of course isn’t great for sleeping partners. It affects 18 million people in the US, and I am one of them.

I was diagnosed about 15 years ago, after doing a sleep study in hospital. I was wired up with all kind of monitors, slept overnight, and found that I was waking around 28 times an hour – I had moderate obstructive sleep apnea. The doctor prescribed a C-PAP machine, which pumps air into the lungs during sleep through a sleep mask covering the face. Some people tolerate this and get used to it, but I hated it.

So I then tried a dental device, a mouthpiece that holds the lower jaw slightly forward to keep the airway open. Miracle! It worked and I could dump the C-PAP! As confirmed by a second in-hospital study, my sleep apnea was officially under control. It was expensive – $1,800 for a dental device – but it was worth it even though I had to pay out of pocket.

The device worked great for several years, even after my dog chewed part of it off. Eventually, I replaced it after I got better insurance; I only paid $300 for the new device. Better still, the necessary before and after sleep studies were now conducted at home using a portable sleep-tracking device.

Then disaster struck. I left the device on a plane! I couldn’t really afford the full cost of a new device, so I started exploring online. Pretty much immediately, I found SnoreRX, which is functionally identical to my lost dental device, except it is self-installed using moldable plastic (like in sports mouthguards). And it cost $99 instead of $1,300. It’s explicitly marked “not for sleep apnea,” because it is not FDA-approved.

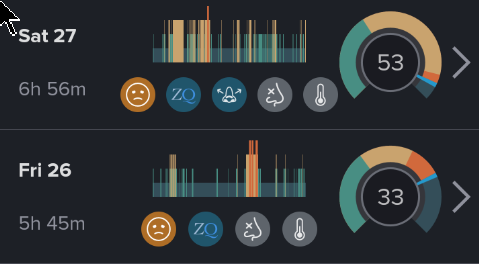

Well, SnoreRX seemed to be working, but I wasn’t entirely convinced, or at least wanted more data. So I looked for a way to track my sleep at home. A number of wearable products do that, from companies like Fitbit, but the product reviews on Amazon seemed spotty. Then I found SnoreLab. It’s a free phone app that tracks snoring via audio recording and analysis (I paid $7 for the premium version). Put the phone down by your bed, turn SnoreLab on, and when you wake up it offers a comprehensive picture of your night’s sleep – every sigh and snort is captured, and for convenience, SleepLab aggregates the data into a single “Sleep Score.”

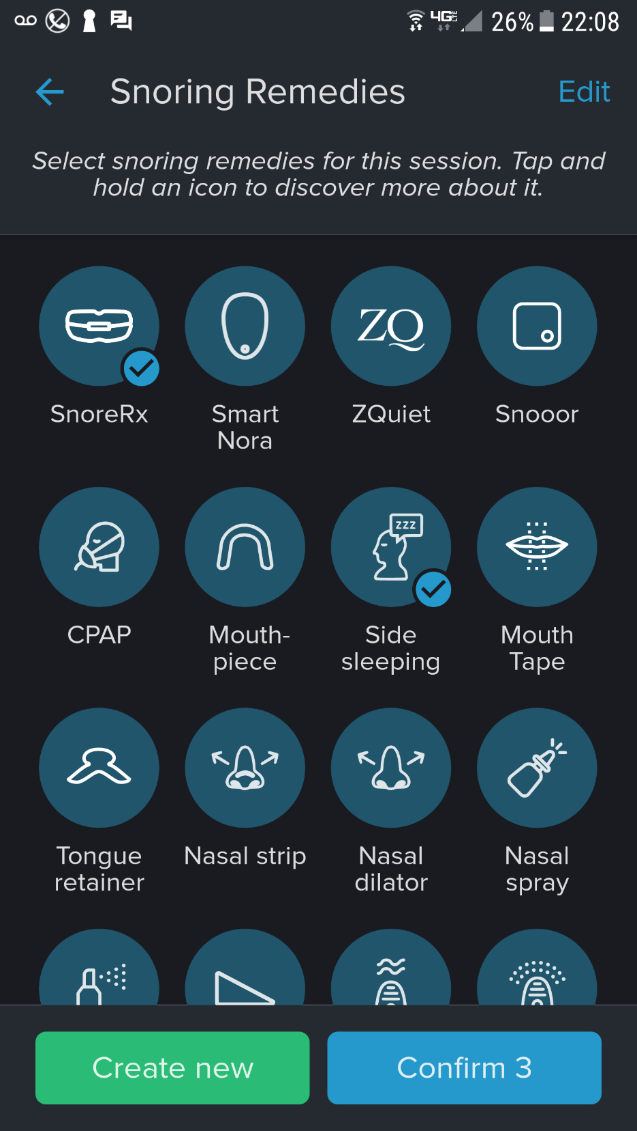

That’s all good, but SnoreLab is much more than an audio recorder. It allows you to track specific interventions – like using SnoreRX, or a chinstrap I tried that failed miserably. And it also lets you track your environment – a late heavy meal perhaps, too much wine, or a cold. These are essentially fields in the database you are building with SnoreLab. And SnoreLab also lets you export the data to Excel where you can do extremely detailed analysis correlating outcomes (snoring) with any combination of multiple inputs (interventions). This is far more granular than peer-reviewed studies.

What did I find? Well, SnoreRX worked. Not perfectly, but pretty well, and probably about as well as the expensive dental device I’d lost. On average, SnoreLab told me that my sleep score had dropped from high twenties to around 10 or even below. But SnoreLab was also indirectly nudging me to try lots of other options – it listed about 20 different interventions on which you could collect data, and those were presumably the most popular solutions for snoring. So, based on the wisdom of crowds, I tried using a bed wedge – lifting the head of the bed about 4-6 inches.

Holy Cow! Transformational. Tilting the bed eliminated snoring: my new score was around 2 or 3. Mostly not snoring at all. Even better, when traveling, I found I could use a blow up bed wedge, and that worked just as well.

One final step. I tried eliminating the SnoreRX mouthpiece. And that worked too – I found that my overt sleep apnea symptoms nearly vanished even without the mouthpiece, provide I was using the wedge. I confirmed this with a couple weeks of SnoreLab monitoring, although today I still use both to effectively eliminate snoring (my wife is very happy about this).

There is plenty learn from this:

- You have to iterate. Only with iteration can the patient adjust interventions and gradually work toward an effective solution. And iteration requires monitoring at home. I would never have been able to find a way without SnoreLab.

- Patients can drive their own treatment. It would never even have occurred to a doctor to suggest that I experiment with sleep apnea cures. But I quite quickly found what works for me. Doctors will have to adjust to a role that is more partner than God.

- Personalized medicine means patient-driven medicine. I am the expert on me, and I increasingly have tools to deepen that knowledge. I can then use it – guided by humans or machines – to find what works for me. Doctors essentially deal in aggregate data – they know what works on average. But I can become the expert on “me medicine,” because I have all the data and all the incentives.

- Tools must be easy to use. If I had to wire myself up to do sleep studies I would never do it. If I had to fiddle with a separate machine I probably wouldn’t do that either. Turning on an app in my phone is entirely doable.

Solving my sleep apnea problem was deeply empowering. I don’t expect to ever walk into a doctor’s office and simply accept a diagnosis or a prescription. And as other apps like SnoreLab become more available for other conditions, I will be using them too for tracking the rest of my health.

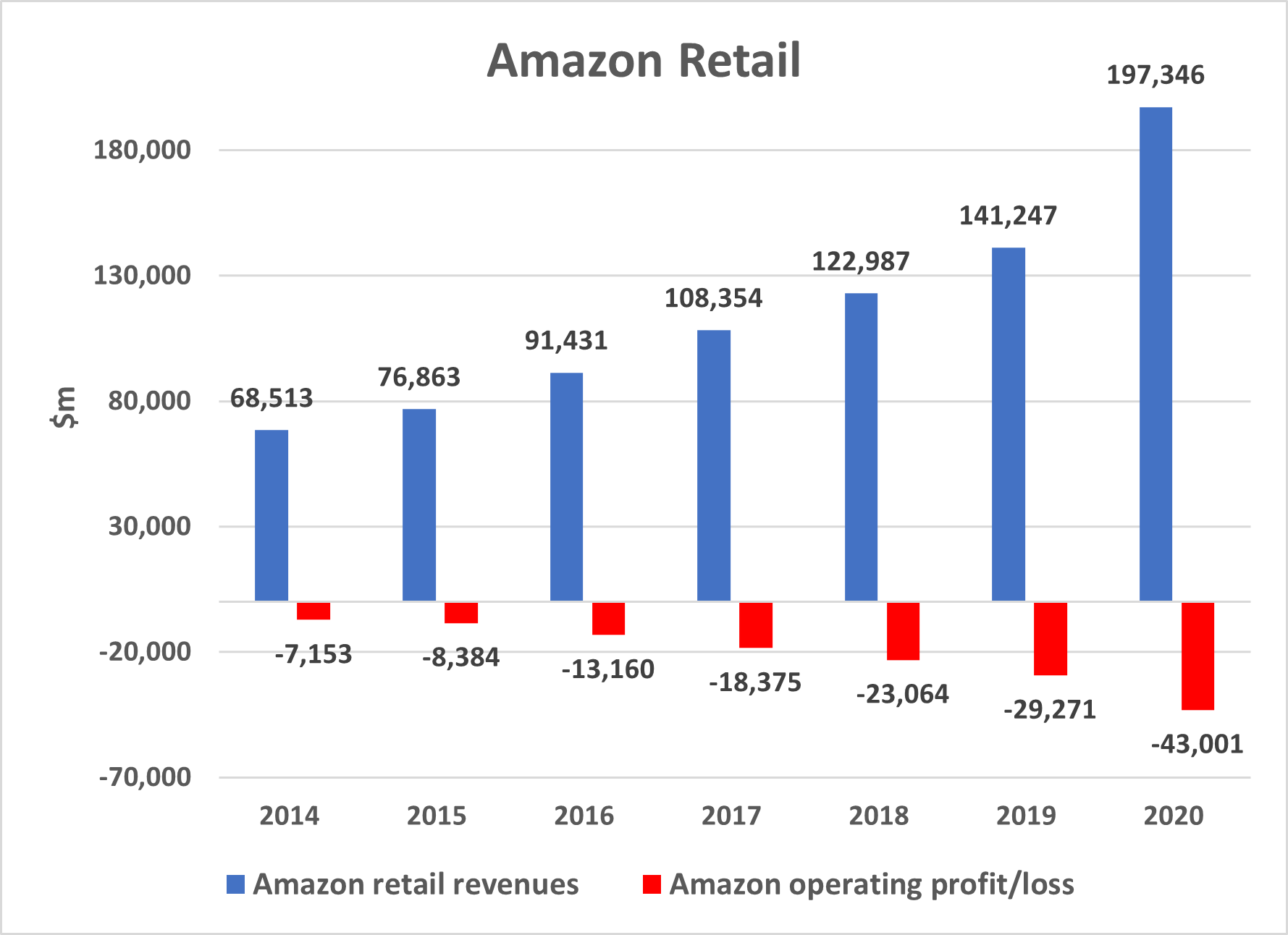

Charts

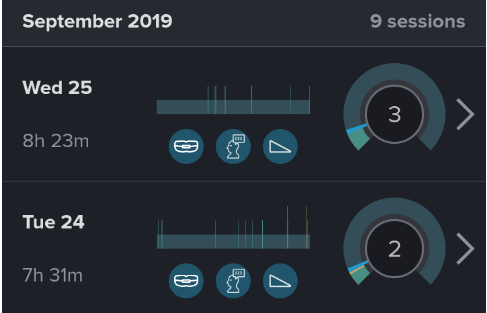

- Initial snoring plot, showing two days

- Possible snoring remedies to track

- Final Outcomes plot